Interview with November 2024 Resident Zach Hill.

Interviewed by Savannah Hodges, Fall ‘24 Intern.

Zach Hill

Zach Hill is an interdisciplinary artist, educator, and curator working between sculpture, drawing, and moving image. He has been awarded the Mary L. Nohl Fellowship and Toby Devan Lewis Fellowship along with residencies at Vermont Studio Center, Bunker Projects, RAIR, Elsewhere Museum, and Stove Works. His work has been exhibited and screened at Haggerty Museum of Art, Milwaukee, WI; Frontera Garibaldi, Mexico City; High Tide and Peep Projects, Philadelphia, PA; Skylab Gallery, Columbus, Ohio; Studio 10, Brooklyn, NY; Comfort Station, Chicago, IL; James Black, Vancouver; and VisArts, Rockville, MD. Hill holds a BFA from the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design, an MFA from the University of Pennsylvania and is currently the Digital Arts & Sculpture Technician at Haverford College. He is the head chef and owner of Zach's Crab Shack, a queer contemporary art gallery hiding within the facade of a campy, beach-side crab stand. Hill lives and works in Philadelphia, PA.

Artist Statement (Brief)

As an interdisciplinary artist, I create sculptures, drawings, and videos that play with material identity, visual perception, and speculative utility. Formally my work uses a queer logic of assemblage to reference various devices or infrastructures coalescing with anthropomorphic objects and iconography. These human-scale hybrid forms enact gestures of looking, pointing, or signaling through their imagined functionality and imply a relationship between the “operator” and subject of said operation.

My sculptural process involves material misuse and mimesis, combining mass-produced items such as furniture parts, metal poles, lawn decorations, and jewelry with fabricated appendages and video monitors….

My drawings, mounted in shadow box frames of various depths, textures, and colors, layer charcoal and colored pencil to carve out ambiguous images. Similar to my sculptures, these energetic fields of mark-making intertwine to hint at the recognizable while teetering on the edge of total abstraction. The framing of these works on paper has grown increasingly sculptural….

In these multidimensional transmutations, I present objects and images that actively misbehave, challenging perceptions and expectations of function, form, and material. This misbehavior encapsulates my practice, which at its core, physically manifests a type of innate, undeniable, and unable-to-be-hidden queerness.

Read the full statement and view more work at: https://zach-hill.com

Interview

Savannah: In your artist statement, you mention that your work “actively misbehaves”. Can you elaborate on this? How do you think your work benefits from “misbehaving?”

Zach: Three words that I often use to describe my practice are misbehavior, misuse, and mimesis. These words all relate back to my experiences as a member of the queer community. Mimesis being something that queer people do to avoid being outed, to blend in for safety, or to learn from one another. Misuse being something we are perceived to do with our bodies through sex. And misbehavior being the way that many people around the world perceive queerness. I take these notions and apply them to the materiality of my work in a variety of ways. I’m interested in faux or confusing surfaces, combining found objects with fabricated elements, and, in general, finding unexpected ways to subvert traditional perceptions of everyday objects. In general, I see sculpture as a type of misbehavior; there’s not always a straightforward logic or reason for my forms to exist, but they do anyway.

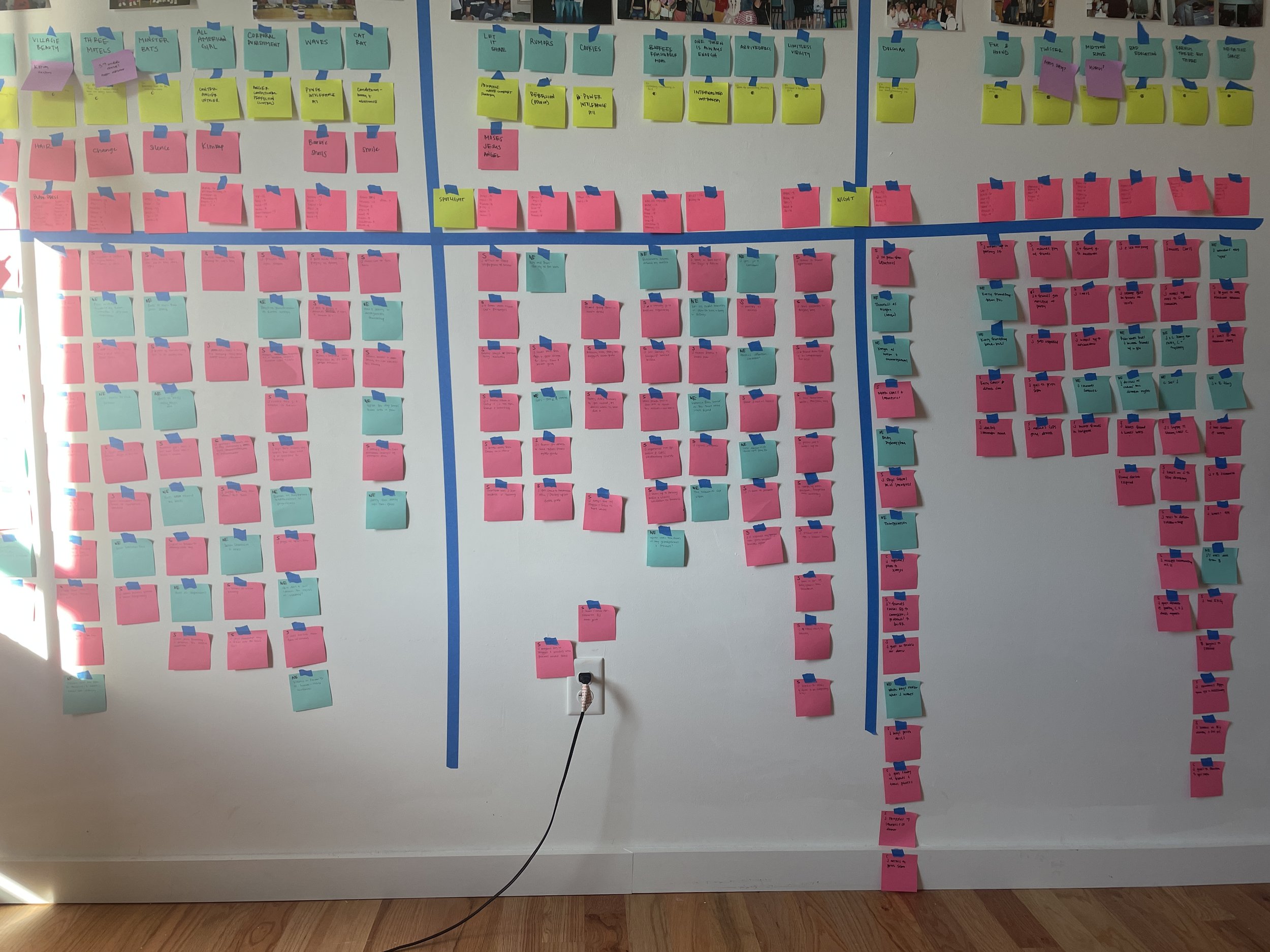

Work in Progress in Zach’s Stove Works studio.

S: You utilize many methods of making in your practice. Do you have a favorite material or method to work with?

Z: Found objects and materials play a huge role in my practice, both as actual things I'm working with and also in the creation of moving images. I’d say that the found or the “surprise” item is my favorite material in the sense that it typically sparks a new project. I’ll often get a bit obsessive, keeping an eye on something for weeks to months before dragging it into my studio. I often walk around and pick up discarded metal or cords I’ve taken the base off of my kitchen table, and I once even stole the old TV antenna off of my apartment building for a sculpture. These objects are like armatures that I can build off of, adding more fabricated elements or combining them with other found materials. The way that I make video work has a lot to do with gleaning or collecting as well. Like most people, I use my cell phone to film all sorts of things that I encounter day-to-day, both mundane and spectacular. Sometimes I do this thinking it will be for art, and other times, I’m just documenting my life or something cool I saw. For example, I’ve animated a screenshot of wildfire smoke radar, worked footage of a burnt-up three-wheeler motorcycle into a sculpture, or simply used these images as formal references to construct my forms.

Muddy Puppy

cast resin, wax, copper paint with green patina, wax, bronze powder, screws

13" x 5" x 7" 2023

S: You use such a wide variety of imagery in your works; from dogs, houses, and umbrellas to less identifiable things like steel apparatuses and assembled kites. Where do you get your inspiration for the imagery?

Z: This is an interesting question because I often feel like my imagery finds itself. I like to start working on something and build up its “ness” throughout the process. I’ll often reconfigure things until they look like something or at least look like something to me. There’s a moment where I go “Oh! That’s a weird spaceship hot rod motorcycle” or “Look, a puppy!” I consider many of my sculptures, particularly those working with larger found metal, to be imagined implements or infrastructures that are also figurative characters. They have functions as well as desires and emotions. I’ve been inspired by a wide variety of things from Galileo thermometers, microscopes, electrical poles, vintage lighting rigs, and everyday objects like a lamp shade, handheld mirror, or fishing rod.

Animality has always been of interest to me and I’ve used representations of domestic and wild animals in various ways. Dogs have popped up most frequently and I think that’s due to their incredibly long history as domesticated animals and the huge place they hold within past and present culture. Canine iconography can be found in every corner of art history so I see depicting these furry friends as a continuation of that. In the USA, the dog is part of the perfect portrait of a nuclear family. My version of a dog is more of a deviant, the animal in the family that kind of resists domestication and tries to return to a type of wildness.

The variety of imagery I use is reflective of this point I’m at in my practice right now of not limiting myself when it comes to anything. If I want to make abstract work I can and if I want to make something representational I can. I’ve developed a lot of different approaches and my use of imagery is part of that.

Spiraling Jewel Girl

looping HD video, outdoor TV antenna, rubber, cords

92" x 50" x 40"

S: Do you have any specific plans or ideas for your time here at Stove Works?

Z: I’m currently working on a drawing and two sculptures. The sculptures are both too large to work on at my home studio so it’s been nice to utilize the space Stove Works provides. One of these pieces uses a vintage lighting rig I thrifted a couple of years ago. The other uses the old base from my kitchen table and has grown into a kind of futuristic motorcycle hovercraft sculpture. I’ve also been developing a couple of drawings that use multiple sheets of paper.

Hot Rod

metal, wood, epoxy, selenite, fuax leather, rivets, reflectors, looping hd video

92" x 80" x 65"

2023