Bio

Jen is a Korean American writer and mental health advocate based in Portland, Oregon, entering into her eleventh year in recovery from alcoholism and bulimia. Her writing focuses on her addiction, exploring the impacts of identity, race, and intergenerational trauma. Through her work, Jen hopes to reach communities of color to destigmatize the stigmatized, decolonize shame, and encourage healing. She is the recipient of HrStry’s 2022 Eunice Williams Nonfiction Prize and has received fellowships from Anaphora Arts and Fishtrap. In 2021, she published a zine through zines + things and her essays can be found, or are forthcoming, in Oregon Humanities, aaduna, and The Rumpus. https://www.jen-shin.com/about

Jen was in Residence at Stove Works during October and November of 2022.

Interviewed by Cass Dickenson

Cass: Why don’t you tell me about yourself?

Jen: I am a writer, and the identities that I write to are being in recovery from addiction and being a woman of color. The memoir I’m working on during my residency is about my experience with addiction and understanding the roots of addiction. That’s really how I see the world, and those are the lenses I use in my work. Those are the things that have impacted me and led me to this journey.

What else? I live in Portland, Oregon, but was born in Chattanooga. I’m also a baker. I’ve been recently baking bread and selling it at farmer’s markets. The baking is sort of a healing process for me since part of my addiction journey has been having an eating disorder, and being able to make food for people and eat food with people has become healing. It’s sort of a full-circle moment for me. I also lead camping trips for people of color and queer people. To see our own representation in nature is really powerful for me.

C: So, how’s that going during your residency in Chattanooga? Are you getting in touch with Chattanooga’s landscape outside of your studio? How are you spending your time outside of your studio?

J: It’s been great to have my residency during the fall because I always hated the summers. You know, when I was growing up I didn’t like being outside. When I was younger I loved it, but as I got older, there was no interest. It was too humid to do anything in the summer. After moving to the PNW, though, I’ve found my own relationship with nature in such a new way. My own spiritual practice involves being really grateful to the earth. In terms of my time with Stove Works, I’ve been walking a lot: to the sculpture fields, for instance. Part of my writing practice is–y’know–30% of it is writing, and the rest is thinking. I can sit and think but being out in nature and observing and feeling present is something that helps me process things. I’ve gone to the sculpture fields, I’ve gone to the river walk, and I saw like 5 great blue herons.

When I was younger, I’d laugh at tree huggers, but now, 20 years later, I’m literally doing that [laughs]. Being outside has been really grounding, and obviously, fall in Chattanooga is the best time to be here. It’s been helpful to have nice weather and be able to take a walk just to clear my head.

C: You’re writing about very personal history in relation to nature. I take it it helps to be grounded in the place you grew up?

J: Yeah! For the past year, I’ve been struggling to write the story of high school. And I’ve been chewing on this for a long time. It’s only a facet of the broader story, but I’ve been needing to crystallize that specific moment of time. It wasn’t until I got here, started walking in the places I used to hang out with friends, or park my car or go to the Aquarium – All of these places have so much memory for me. It’s what I really needed to put myself back into perspective: what were the good things? What were the bad things?

I was really nervous coming back to Chattanooga because of racism because of being Asian in a predominantly white area. It was easy to say, “oh y’know the racist south” and all that, but I can view it more holistically now, with the right vocabulary and perspective. I’ve been in recovery for a decade so being able to have the time and space to process this has let me write new material that I needed to get out. That can be kind of difficult, and I don’t like to force things, so being able to process and listen to myself back here has been very, very helpful to bring myself back.

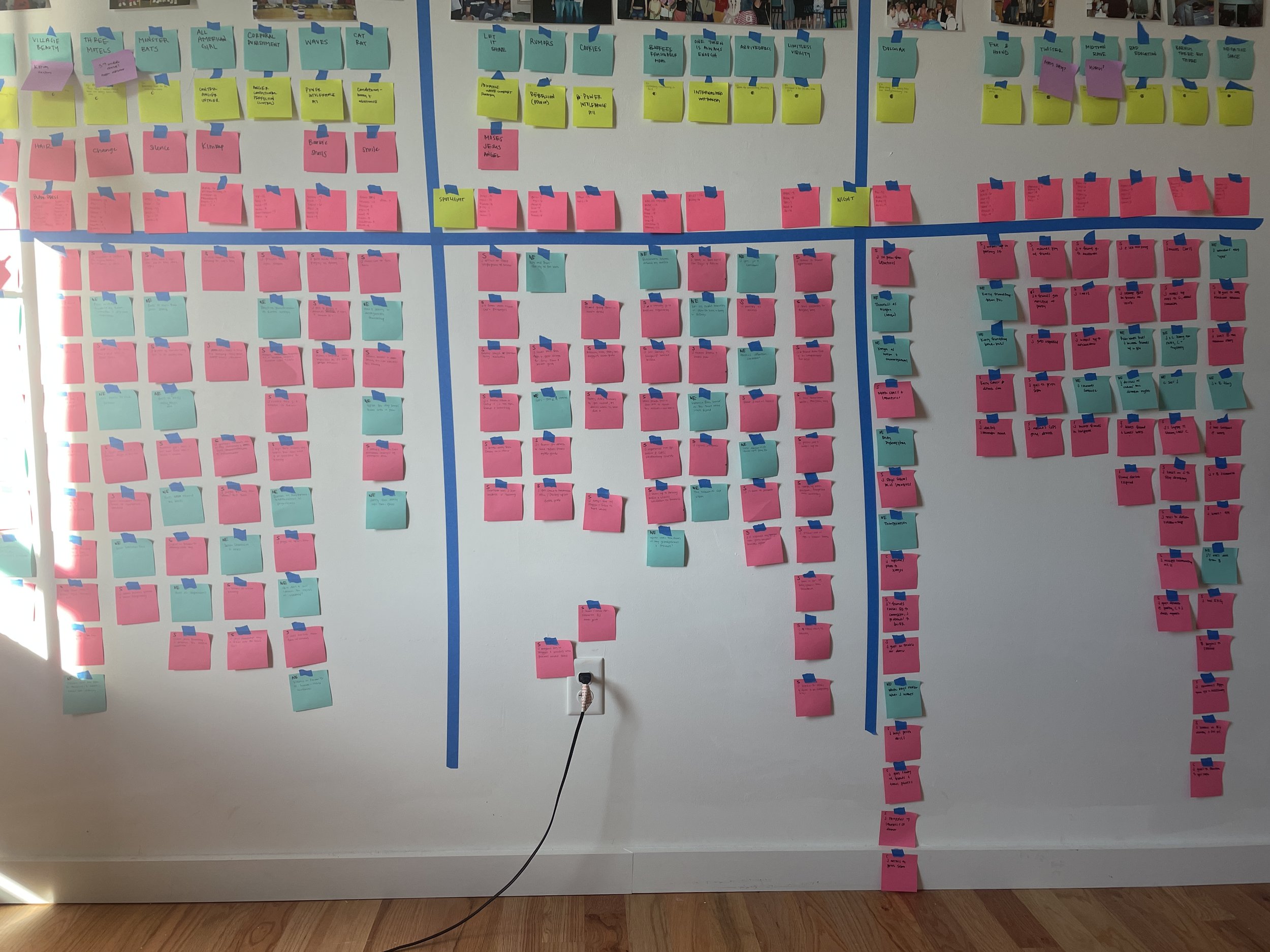

C: I can tell from your studio knowing these photos or these notes happened where we are now feels really familiar.

J: Yea, totally.

C: Anything else you want to tell us? Things we can look forward to after your residency?

J: So, like, 75% of the memoir is just setting up the experiences that led to my addiction, and 25% of it is devoted to having the addiction. I feel like a lot of literature is about the neverending suffering of addiction, so that’s not something I feel like I need to do. I want to explore the experiences that shape addiction. I kind of wanted to be seen, but I also wanted to be invisible. I wanted to be Asian, but I also wanted to be accepted by White people.

C: So, like sidestepping putting yourself on a pedestal?

J: Yea, my addiction sort of gave me that experience. Getting, you know, blackout drunk was like a form of disappearing. Those are the two poles that I’m speaking to. What are the ways that I was trying to assimilate, and what are the ways I was trying to cope? I just finished my first draft, so I’m going through high school right now. I’m using my second month to start cleaning up those parts of the book that need cleaning up.